by Sara Saybo

If Cinderella Were A Socially Awkward Indian Kid With Autism

I had one of my most epic meltdowns last month–the kind that pins you down like a wild animal, in your face, fangs drawn. It was all about seeing someone with my identity speak our truth to power–a phenomenon I imagine people of color feel all the time when someone of their race excels in some way in the world. A kind of validation, or pride, in the face of such astounding adversity. The grace of being seen, represented, elevated. Being a white person, this was a new experience for me. Being a white person, I don’t see another white person excel at something and feel personally validated or proud in any way, ever, by virtue of our shared skin color. On the contrary: given that so much that is wrong with the world is perpetrated at the hands of white folk, what I’m more accustomed to in that regard is feeling shame for my race, not pride. Shame that I’m white, wishing my skin weren’t the same color as these abhorrent men (let’s face it, it’s mostly men…and mostly white) who perpetrate crimes against humanity as their daily bread.

I had one of my most epic meltdowns last month–the kind that pins you down like a wild animal, in your face, fangs drawn. It was all about seeing someone with my identity speak our truth to power–a phenomenon I imagine people of color feel all the time when someone of their race excels in some way in the world. A kind of validation, or pride, in the face of such astounding adversity. The grace of being seen, represented, elevated. Being a white person, this was a new experience for me. Being a white person, I don’t see another white person excel at something and feel personally validated or proud in any way, ever, by virtue of our shared skin color. On the contrary: given that so much that is wrong with the world is perpetrated at the hands of white folk, what I’m more accustomed to in that regard is feeling shame for my race, not pride. Shame that I’m white, wishing my skin weren’t the same color as these abhorrent men (let’s face it, it’s mostly men…and mostly white) who perpetrate crimes against humanity as their daily bread.

So to see someone like me talk about what it’s like to be us, to break the code of silence around our shared identity, and in such a powerful way, and to an entire auditorium of people pounding and roaring vehement in their adoration of his brilliant weirdness… I had one of my most epic meltdowns that night. But more about that later.

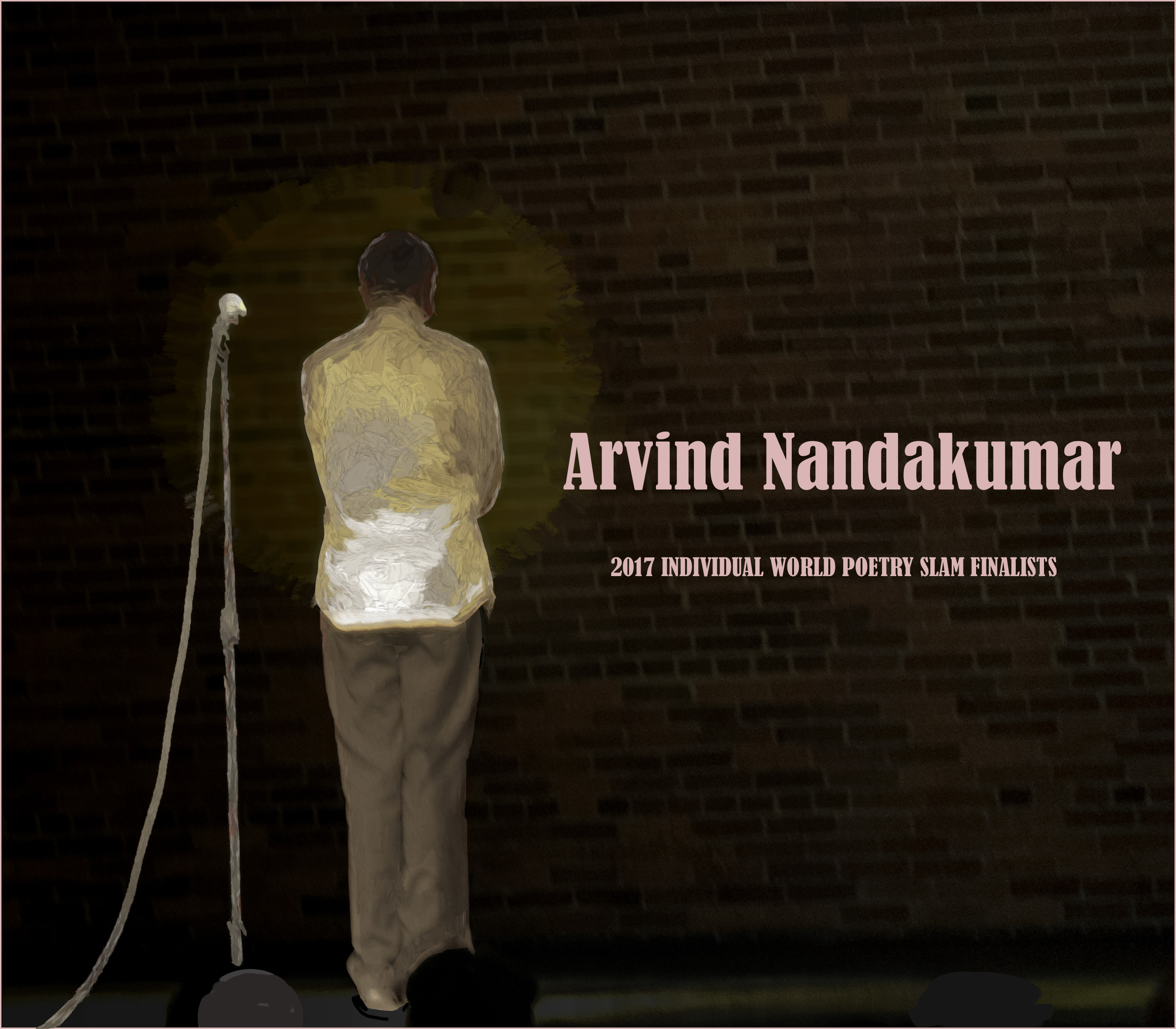

It happened after Spokane made history at the iWPS Competition that was held here Oct 11-14, 2017 (Individual World Poetry Slam). History for people of color, and history for people with Autism. Think the slam poetry version of baseball’s Game 6 in the World Series. Veteran attendees exclaimed with delight and delirium: “I’ve been to so many iWPS, and I’ve never seen anything like this!” With 96 veteran poets from around the globe converging on our little hamlet for the title of World Slam Champion, the person who took the title from all those veteran poets turned out to be a newcomer out of Berkeley by the name of Arvind Nandakumar, a 20 year old Indian-born college student diagnosed with Autism.

Let me tell you, you haven’t lived until you’ve sat in an auditorium full of stomping screaming slam fans from around the world chanting “TEN! TEN! TEN!” at the judges on behalf of the least likely oddball underdog to be receiving such acclaim and mass solidarity. Arvind got his perfect score–all five judges gave him the highest ranking of 10 points for his piece, beating out 14 of the final competing poets (12 of whom were black–diversity hits Spokane!!).

Word has it that he is iWPS’ first Asian/Pacific Islander slam champion. But how this humble, mild-mannered misfit managed to capture the hearts of all these hard-scrabbled miscreant world-worn seasoned artist hard-asses is the real story here.

Word has it that he is iWPS’ first Asian/Pacific Islander slam champion. But how this humble, mild-mannered misfit managed to capture the hearts of all these hard-scrabbled miscreant world-worn seasoned artist hard-asses is the real story here.

In order to explain that story, however, (and my subsequent meltdown), I have to fill you in on some of the history of slam, so you can appreciate the context and power of this young man’s historic and transformational victory. You have to understand, slam poetry competition has a history and a subculture all its own–largely honed by urban people of color, frankly. (Yet another American art form largely influenced by African Americans and other people of color–thank you again, Black America.) Started in the 80’s in Chicago by working class poet Marc Smith, later taking hold at New York’s Nuyorican Poets Cafe and in San Francisco, it has roots as a real street-art sort of voice of the people, speaking truth to power. (Usually at the top of their lungs into a very loud microphone.) No topic is off limits in the slam scene–in fact, the more raw and seedy and controversial and scandalous and unspeakable the topic, the better. Exploring identity, experience, and speaking truth to power are its hallmarks.

Yet after decades of building its art form, certain styles and rules and trends started to take hold in the slam scene. Certain “tricks” for winning began to emerge, largely because the nature of the slam competition itself relies on the zeitgeist of its audience as barometer for who wins. (Matches are scored by random audience members who are asked to be judges for the evening, who may have never attended a slam competition before in their life. In fact, some say the less the selected judges know about poetry or slam itself, all the better. The often repeated line at every slam is, applaud the poet not the points. As in, the points are just an excuse to come together and listen to some pretty rockin’ poetry. Er, well, SUPPOSEDLY. And therein lies the rub.)

Because over time, competitors began to see which kinds of poems tended to win, and which kinds of tactics tended to score the highest, so that eventually, slam poems began more and more to be crafted for points, rather than possessing the most artistry or being the most authentic expression of that person’s own voice. This led to a lot of competing poets sounding the same, like there’s a winner’s template, and people who wanted to do well in the slam community began to employ this template, whether by intention or simply osmosis.

Others in the slam community resisted this tendency, saying it was a cheap shot, and watered down the diversity and the power of the poetic voice in the scene. So that for awhile now, these different camps in the slam community argue about what kinds of poems are authentic, and what kinds of poems are catering to points. It’s gotten to the point where one is almost trading the respect and awe of one’s fellow poets for the glory of scoring high points from the audience. One would think those should be one in the same, and ideally they would be, but this pull between authentic expression and contrived performance is something the scene has been wrestling with for awhile now. It’s a real fine line that long time competing poets need to walk: be original enough to stand out and earn the respect of your slam community (and yourself), but template-y enough to score high with the public and make a name for yourself.

Because here’s the thing: the slam scene has since grown large enough, that it can be lucrative for those at the top–paying gigs at open mics around the world, where they can also sell their chapbooks, t-shirts, stickers, audio/video cd’s at venues or online. So the competition is fierce, and the competitors (and their fans) are serious about it. Livelihood serious. Fame serious. Legacy serious. In fact, one of slam’s most beloved iconic winners from the 90’s, Shane Koyczan, appeared in the opening ceremonies of the Olympics in Vancouver in 2010, for chrissakes, 3 stories up atop a giant revolving piece of stage, replete with lights and pyrotechnics and in the middle of all those hundreds of dancing costumes. (Google it: Canadian Slam Poetry Olympics, and see for yourself.) In other words, slam poetry has arrived. Even if only in the midst of its own identity crisis: are those at the top the best poets, or simply the most popular? And who’s to say there’s a difference, if beauty (or art) is in the eye of the beholder? Enter one Arvind Nandakumar, and just by the seat of his pants. A few days before the competition was to begin, he wasn’t even slated to be one of the competing poets. He had to compete in what is called The Last Chance Slam the night before competition was to begin in order to win his place among the 96 competing poets. And even then, upon winning, the hat had to be passed around the venue to collect enough money to pay for his $150 entrance fee. (The hat magically acquired $156 exactly, as though fate had a hand in the epic upset win that was to transpire.) Three days later, after an unprecedented hour-long nail biting tie-breaker process at the end which left some of the judges moved to tears by his victory, he was crowned iWPS 2017’s Slam Champion.

Enter one Arvind Nandakumar, and just by the seat of his pants. A few days before the competition was to begin, he wasn’t even slated to be one of the competing poets. He had to compete in what is called The Last Chance Slam the night before competition was to begin in order to win his place among the 96 competing poets. And even then, upon winning, the hat had to be passed around the venue to collect enough money to pay for his $150 entrance fee. (The hat magically acquired $156 exactly, as though fate had a hand in the epic upset win that was to transpire.) Three days later, after an unprecedented hour-long nail biting tie-breaker process at the end which left some of the judges moved to tears by his victory, he was crowned iWPS 2017’s Slam Champion.

It feels beautifully appropriate that someone on the autism spectrum is the one who single handedly broke through the decades-long glass ceiling of “performing for points” that has plagued the slam community and iWPS for so long now. His win was like a win for the little guy–for all the poets who have remained true to the sound of their own voice regardless of whether this would win them audience approval and its subsequent fame. His win ushers in the long-time-coming transformation back to its authenticity roots that the slam scene has been starving for, for so long now.

I explain the inner workings of the slam scene–and the poignancy of his win specifically–in order to capture what I believe lies at the heart of what it is to be on the Autistic Spectrum: authentic innovation. We tend to see things differently than other people. We tend to see the things others don’t see. We tend to be vehemently verbal about what we see. Which, while exasperating and taxing to our loved ones and community, often offers transformative insight and focus to whatever our area of interest may be. Think Einstein’s theory of relativity, as the most famous example of this Autism Spectrum genius. Or Alan Turing’s breaking of the enigma code, essentially winning World War II for our side. If it weren’t for us, so many of the world’s advancements and leaps in innovation would be nonexistent. It is no surprise to me that the person to pull off such an unlikely upset at iWPS finals is someone on the autism spectrum. Breakthroughs are our specialty. Which is kind of the whole point of our existence, and our value.

I explain the inner workings of the slam scene–and the poignancy of his win specifically–in order to capture what I believe lies at the heart of what it is to be on the Autistic Spectrum: authentic innovation. We tend to see things differently than other people. We tend to see the things others don’t see. We tend to be vehemently verbal about what we see. Which, while exasperating and taxing to our loved ones and community, often offers transformative insight and focus to whatever our area of interest may be. Think Einstein’s theory of relativity, as the most famous example of this Autism Spectrum genius. Or Alan Turing’s breaking of the enigma code, essentially winning World War II for our side. If it weren’t for us, so many of the world’s advancements and leaps in innovation would be nonexistent. It is no surprise to me that the person to pull off such an unlikely upset at iWPS finals is someone on the autism spectrum. Breakthroughs are our specialty. Which is kind of the whole point of our existence, and our value.

And yet, we suffer, as individuals and as a community, because we have trouble socially, we don’t fit nicely into the norms of the dominant paradigm, which creates havoc and stress for us and those around us who don’t understand our needs and sensitivities. Who don’t see the value in supporting our ways of being different than neurotypical folks. (Those on the spectrum are referred to as neuro-atypical, while the rest of you are neurotypical.) For example, Einstein’s social life was famously a complete chaotic disaster, even though he is heralded as one of our most beloved and wise thinkers of all time. Alan Turing suffered a lifetime of exclusion and ridicule for his atypical social behavior and awkwardness–a life that ended, as too many spectrum lives do, in suicide. Even though we owe our freedoms in large part to him. How many world-saving innovations have been or will be bleeding themselves onto the lifeless floor of their bathrooms, or aborted through genetic testing, because the way autistic people behave in the world is seen as undesirable or even abhorrent?

Arvind spoke so eloquently to the awful isolation of this dichotomy–how we are lauded for our brilliance, and yet loathed for our sensitivities and quirks. He spoke to the pain of this isolation of being used for our intellectual skills while being shunned for our lack of social skills. He challenged the status quo of the national organization Autism Speaks, and their stance of finding a “cure” for this “disease”, that many on the spectrum find dismissive and offensive, tantamount to a kind of genocide, or at best, eugenics. As though what we are is wrong, as opposed to simply, different. Sometimes different can be better. Valuable. Even, lovable.

Arvind spoke so eloquently to the awful isolation of this dichotomy–how we are lauded for our brilliance, and yet loathed for our sensitivities and quirks. He spoke to the pain of this isolation of being used for our intellectual skills while being shunned for our lack of social skills. He challenged the status quo of the national organization Autism Speaks, and their stance of finding a “cure” for this “disease”, that many on the spectrum find dismissive and offensive, tantamount to a kind of genocide, or at best, eugenics. As though what we are is wrong, as opposed to simply, different. Sometimes different can be better. Valuable. Even, lovable.

I came home after the iWPS Slam Finals so moved and stunned and blown away… It was a powerful thing to see an entire auditorium loving this oddball spectrum kid talking about his asexuality, and his need for his parents still, and the “anxiety poison” in his head that won’t quiet down without their hand on his forehead. He spoke about what it was like to be a person of color in an already marginalized group, and how all the poster children for autism tend to be white, and what that means for him. He spoke about the struggle with social anxiety, finding the right thing to say, failing so many times over it becomes the trauma brick wall we hurl ourselves into daily in an effort to connect. I related to so many of the things he talked about–how painful it can be to live in bodies like ours, and to be summarily rejected for it on top of it. So to be hearing all these painful truths spoken to an entire auditorium of all these remarkable and accomplished artistic people pounding and roaring vehement in their adoration of his brilliant weirdness… I went to bed that night weeping myself into a meltdown, thinking, wow, they all love him for his Aspergers… and hate me for mine.

I’ve lived in Spokane for over a dozen years now and I still haven’t found a place where I belong–my aspie proclivities often misunderstood by neurotypical folks, and hidden from my fellow aspies. If you’re a person of color, you can scan a room and know which people are your racial tribe. If you’re queer, you can go to a bar or a support group dedicated to your orientation in order to find people like you. But being on the autism spectrum…most of us aren’t “out” about our identity. (Thanks to the stigma perpetrated by shows like “The Big Bang Theory”, which spectrum folks see as tantamount to white actors in blackface–the way they over exaggerate the worst stereotypes of our identity for a cheap laugh, and fail to represent the hard realities of our experience.) We tend to keep quiet about this aspect of who we are. And even if we are out, we can’t exactly scan the room to find out which ones are of our aspie tribe. We don’t exactly have a “look” or a socially agreed upon “uniform” the way some other groups do.

There’s a saying in the autism community, as Arvind reminded us in one of his poems: if you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism. We are all so drastically different from one another, which adds to the difficulty of finding connection with each other. Our interests and temperaments and needs and levels of functioning vary so drastically. Really the only sure thing we have in common is that we see things differently than neurotypical folks do, and we have sensitivities that neurotypical folks don’t have, and therefore suffer the extreme isolation that comes with our resultant social anxiety. So that really…the way we would find support and friendship and community isn’t necessarily with each other, so much as, with whatever neurotypical folk share our same area of interest or our same community involvements. Which would require neurotypical folk to cross the chasm of social norms discrimination and find a way to embrace and include us anyway. Even though we’re different. Um…I mean, valuable. Um…I mean, lovable.

Maybe one day Spectrum Awareness Week will be celebrated in the same spirit in which we celebrate African American History Month or National Coming Out Day. Maybe one day we’ll have our heroes enshrined for their neuro atypical genius in the same way we honor Martin Luther King, Jr. or Billie Jean King for their respective identity affiliation. Maybe one day Autism Speaks’ search for the cure will be seen in the same way as the Third Reich’s ethnic cleansing campaign. Maybe one day, neurotypical schoolchildren will line up eagerly waiting to acquire the autograph of their hero–the long-since famous Autism Spectrum Poet and Activist: Arvind Nandakumar.

Maybe one day Spectrum Awareness Week will be celebrated in the same spirit in which we celebrate African American History Month or National Coming Out Day. Maybe one day we’ll have our heroes enshrined for their neuro atypical genius in the same way we honor Martin Luther King, Jr. or Billie Jean King for their respective identity affiliation. Maybe one day Autism Speaks’ search for the cure will be seen in the same way as the Third Reich’s ethnic cleansing campaign. Maybe one day, neurotypical schoolchildren will line up eagerly waiting to acquire the autograph of their hero–the long-since famous Autism Spectrum Poet and Activist: Arvind Nandakumar.

By Sara Saybo

Portraits by Robert Lloyd