In Times of Trump Dismantling American Government

Comprehensive Strategies to Regain Control and Protect Democratic Institutions from Systematic Dismantling

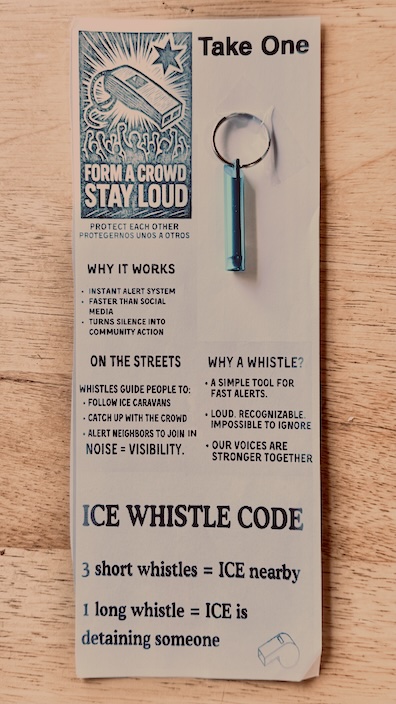

Freedom of Assembly – A Constitutional Right

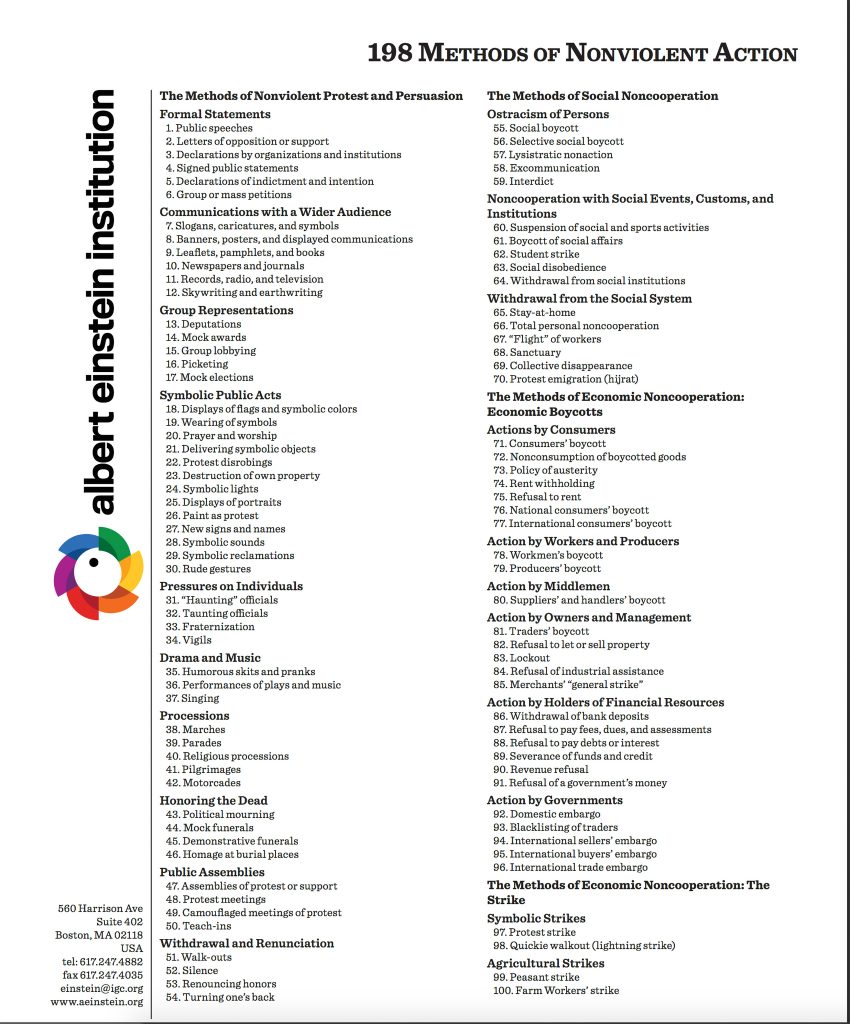

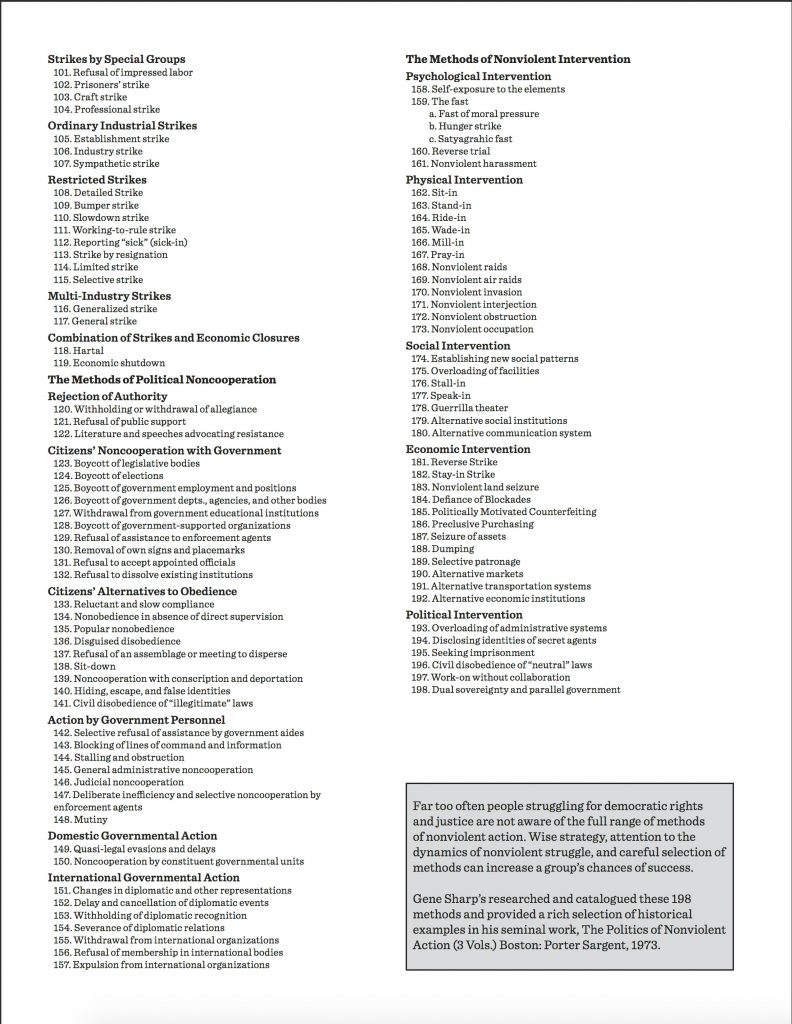

# Immediate Action Strategies

## 1. Legal and Constitutional Mechanisms

– Utilize judicial review to challenge unconstitutional executive actions, as established by Marbury v. Madison [[1]]

– Leverage existing checks and balances systems to limit executive overreach [[2]]

– Employ legislative oversight tools, including:

– Congressional hearings

– Investigations

– Strategic use of funding controls [[2]]

## 2. Civil Society Response

– Engage with organizations like Civil Service Strong and Partnership for Public Service that specifically work to protect civil service [[3]]

– Support watchdog organizations and legal advocacy groups like Protect Democracy [[4]]

– Mobilize grassroots movements and civil society organizations to:

– Monitor government actions

– Expose corruption

– Lobby for governance reforms [[5]]

## 3. Institutional Protection Measures

### Government Workforce Protection

– Support initiatives defending civil service against political interference

– Work with unions and professional associations to protect government employees

– Document and challenge illegal terminations or restructuring [[3]]

### Democratic Process Protection

– Safeguard election integrity through:

– Protection against voter suppression

– Combating disinformation

– Maintaining election infrastructure [[6]]

## 4. International Cooperation and Support

– Engage with international organizations like International IDEA and UNDP’s Democratic Governance [[7]]

– Utilize international pressure and accountability mechanisms

– Learn from other democracies’ experiences in resisting authoritarian attempts [[8]]

# Long-term Strategic Approaches

## 1. Develop a National Democracy Strategy

– Create a comprehensive plan integrating democracy protection into:

– Economic policy

– Social policy

– Technology policy

– Diplomatic relations

– Military considerations [[9]]

## 2. Build Cross-sector Alliances

– Form coalitions between:

– Civil society organizations

– Legal professionals

– Academic institutions

– Business leaders

– Pro-democracy politicians [[10]]

## 3. Public Education and Engagement

– Launch public awareness campaigns about democratic institutions

– Educate citizens about their rights and democratic processes

– Foster civic participation and engagement [[5]]

## 4. Media and Technology Strategy

– Support independent journalism

– Combat disinformation through fact-checking initiatives

– Engage technology companies in protecting democratic processes [[11]]

# Success Indicators from Historical Examples

Historical examples show that democratic institutions can recover from systematic dismantling attempts. Key lessons include:

1. **Post-WWII Germany and Japan**: Successful reconstruction required:

– Strong constitutional frameworks

– International support

– Economic rebuilding

– Democratic institution building [[12]]

2. **Eastern European Transitions**: Demonstrated the importance of:

– Civil society movements

– International support

– Economic reforms

– Democratic constitution development [[12]]

# Current Public Support

Recent data shows potential for successful resistance:

– High public demand for government reform (49% Democrats, 83% Republicans) [[13]]

– Strong electoral responses against anti-democratic actions

– Growing concern about institutional integrity across political spectrums [[14]]

The success of these strategies depends on coordinated action across multiple sectors and sustained commitment to democratic principles. The research suggests that combining legal mechanisms, civil society action, and international support provides the most effective approach to protecting and restoring democratic institutions.

Like this:

Like Loading...